Powered by a mid-mounted Ford V8, giving 260bhp with its Shelby-Cobra modifications, it had a four-speed Colotti transaxle gearbox with gear selection by a set of three cables, like the column-change arrangement on the contemporary Ford Cortina. Directly borrowed from the Cortina were the famous ‘Ban the Bomb’ rear lights. With its slippery body, standing just 40in high, a top speed of 180mph was predicted. That car could have taken on Ferrari and won many races in 1963, including the Le Mans 24 Hours, but luck wasn’t with it. Without doubt, proper funding would have realised the potential of this superb car immediately. The gearing, for example, turned out to be much too low for Le Mans, but nothing could be done about that by the hard-pressed Lola team in the time available.

Produced on a shoestring budget in a tiny workshop in Bromley, it was driven on trade plates to Le Mans by Eric himself. His assistant designer was a young Tony Southgate, later to go on to many great achievements in his own right. Tony once told me that he remembered leaving for Le Mans at the last minute, sitting in the passenger seat and unable to move because all the spares had been wedged in on top of him.

After taking a scheduled flight across the Channel, they had a minor fright. ‘The front wishbones were bolted up on rubber bushes,’ says Eric, ‘and the French roads were somewhat undulating then, which unscrewed the nuts!’

He pulled up when the car began to feel rather strange, and luckily before it all came apart. All they had to do was to tighten up the nuts so that it wouldn’t happen again.

The behaviour of the Mk6 on the circuit was excellent despite very little testing, but Eric’s designs tended to handle well from scratch. That was certainly the case with the Mk6, which Eric claims was a car that gave a driver immediate confidence as soon as he left the pit road. Many years later, I raced that very car myself at Snetterton and it really was fabulous to drive, even when aquaplaning occasionally in a torrential downpour.

Collaborating with Ford

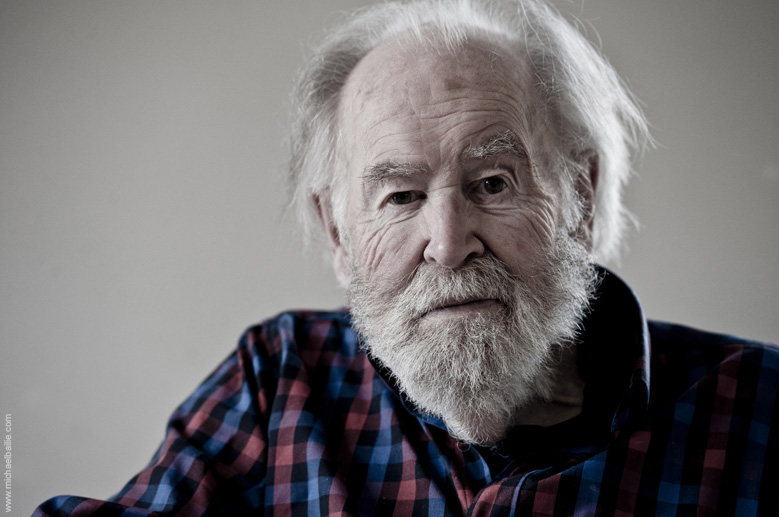

In 1963, the Ford Motor Company was keen to take on Ferrari at Le Mans without delay. When the Mk6, despite its modest budget, showed great promise at Le Mans in the hands of Richard Attwood and David Hobbs, its potential was immediately appreciated in Dearborn. It did not matter that David Hobbs had experienced gear selection trouble at the Esses and overturned, putting the Lola out of the race. An impressed Ford Motor Company offered Eric a two-year contract that would take his services and everything to do with Lola Cars, exclusively and completely, into the Ford GT works programme. Famously, the Mk6 was to form the basis of the original GT40, which did eventually lead to the famous victories at Le Mans. However, within a year Eric had left the project, and this visit to his home seemed a golden opportunity to seek his inner thoughts about what really happened back then.

‘The Ford involvement was very welcome,’ says Eric, ‘because we needed the money… but it tended to break the spell, if you like.’ Eric had been following his own instincts, as he puts it, and difficulties arose with the way that things were done in the vast Ford corporation. Late in 1963, he had moved to work within Ford Advanced Vehicles in Slough, where the Ford GT project was being managed by the legendary John Wyer, but the chief designer was Ford’s Roy Lunn, whose first act was to present Eric with a totally different suspension dynamic for the car.

This was once a very sensitive area and, still inclined to tread carefully, I ask: ‘Other people have told me that the American designers were inexperienced in this field and didn’t really know how to do the calculations properly. Is that right?’

This produces a long, long pause, while Eric considers his response. Eventually, he says, rather quietly and slowly, ‘Basically… yes.’ There is another long pause, before he adds, ‘They put their suspension onto the Mk6, which ruined the handling. So I changed part of it back, just to check where I was, and that was the cause of my first serious falling out with Roy Lunn, when he gathered what I’d done.’

The intended co-operation had got off to a bad start, but things soon got worse: ‘The next big problem – there were lots of small ones but this was the next big thing – was that they sent us a body shape that clearly wasn’t going to work. I explained the situation to John Wyer, who simply advised, ‘Give them what they want.’ I decided that I should go to Dearborn and explain the problem to the Ford people. John Wyer agreed to that, and I went, but it got me absolutely nowhere.’

He does not mention it now, but subsequent events proved that Eric was right there, too, because the original GT40 required serious alterations when the aerodynamics proved extremely unsatisfactory.

After another thoughtful pause, Eric added: ‘Another disagreement with Roy Lunn was over the construction of the new Ford GT’s monocoque. It ended up as a sort of production road car job, all in steel, whereas what you want for racing is something much lighter.’

As the Ford engineers were determined to take their own path, it was obvious to all concerned that the relationship with Eric had no future. By mutual agreement, his personal contract was terminated early: ‘And they paid us… which was important! It was a shame because it could have been a wonderful opportunity, both for us and for Ford.’

After that abrupt break, Eric rapidly picked up where he had left off – he regrouped in premises in Slough, designing, building and selling racing cars. Success followed quickly in many different fields: Graham Hill won the 1966 Indianapolis 500 in a Lola run by Mecom Racing and, in the same year, John Surtees won the first Can-Am Championship with his Lola T70-Chevrolet.

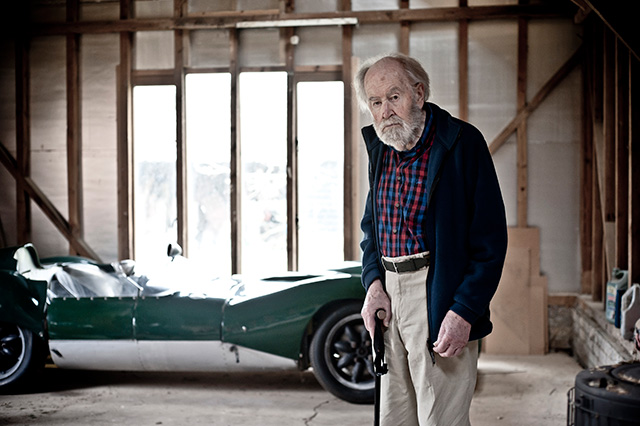

Eric moved the company to bigger premises in Huntingdon and carried on for another 33 years until 1999, when the company had to be sold to Martin Birrane.

The purpose of our work here at Broadley Automotive is to mark Eric’s work for many years to come and to produce some of his earlier cars, so that the vintage racing scene can continue to enjoy these fantastic Broadley designs.